Inevitably, any tangible encounter with the past, bumps up against the intrusive present. In a city like Toulouse—in any city, steeped in history, yet thriving in the present moment—it’s sometimes impossible to reconcile the richness of the past with the jarring intrusion of modernity: Those snarling trucks and shrieking motor-scooters; flashily-fronted restaurants, and tourists posing with their selfie-sticks…. If only, I think, it were possible to scrape away the layers of modern life and get down to the pentimento beneath, back to a realm untouched by the intervening centuries.

On the other hand, I console myself, if I actually could strip one of these cities, like an artichoke, to its ancient heart and literally step into the past, I might run the risk of facts getting in the way of my story and paralyzing my invention. Possibly, for the purposes of a novel, ’m better off simply using those remaining vestiges of the distant past—the odor of old brick, the enduring brilliance of the cerulean sky, the sensation underfoot of paving stones hollowed in places by centuries of boot-and-sandal-shod feet—an affirmation that the past, as I’ve imagined it, is somewhat accurate.

In Toulouse, for instance, a 13th-century monastery garden enclosed by arcades of columns looks exactly like the backdrop of a scene I’d already written in a monks’ garden, where a villainous character sits serenely peeling an apple that he plans to infuse with poison plucked from a nearby plant. To me, a totally recognizable location—although I’d never previously passed that way, except in imagination. Just as I’d been startled on a previous trip, to the Western U.S, by the familiar décor of a hotel bar I thought I’d invented.

But whatever the upshot of the journey—whether undertaken to reach back into the past or to scout locations for some future adventure now only in the planning phase—having a purpose enriches the experience, turns a mere destination into a part of some grand plan or organizing principle—un but, if you like.

I recall as a teenager reading John Steinbeck’s “Travels With Charley” and being impressed. Not only did Steinbeck outfit a small truck as a camper-cum-sleeper to live in on the road with his dog, he organized his itinerary around a geographical exploration of the mood of America, in the lead-up to the presidential election of 1960.

For some reason I now forget, he began his odyssey in northern Maine, before proceeding westward and then south and back to the east around the periphery of his native country. Much that Steinbeck learned over the course of his lengthy road-trip, I also forget. What still sticks with me is the value he placed on having a plan to hang his hat on, a question to direct the quest, a grail of some kind—holy or otherwise—to propel his journey.

Of course, attempting to retrace the footsteps of a 13th-century saint feels less like a road-trip than an old-fashioned pilgrimage. For instance, to the cliffside shrines at Rocamadour whose long, steep staircase Saint Dominic allegedly ascended (on his knees) in 1219, in search of the Chapel of the Black Madonna, during his final trip north from Languedoc to Paris—thence, to depart France forever and establish new headquarters in Bologna.

Henry II of England’s pilgrimage, more than half a century before Dominic’s, is noted at Rocamadour. There is also a plaque, commemorating the 16th century visit by Jacques Cartier and his crew, specifically to pray for relief from the scurvy on their voyage.

Yet, I did not locate Dominic among all the statues of saints in any of the chapels. Nor did I find any references to him in the wall text documenting the history of the many “pelérins” who’d passed through Rocamadour over eons.

Dominic’s absence was a bit disappointing. Still, when it comes to quests, it ultimately doesn’t matter whether or not you find your grail; the search is all. Lord knows, in the past, I’ve encountered glitches in even my best-laid itineraries: A search for the statue of Greyfriars Bobby in Edinburgh that sent my companions and myself far off-course into the suburbs, thanks to a faulty tourist-department map; a driving trip to the homes of several writers of the American South, only to find the Asheville boyhood home of Thomas Wolfe closed because of a recent fire, and William Faulkner’s home in Oxford, Mississippi similarly shuttered for renovations. And the vaunted “museum” in a former residence of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald in Montgomery, Alabama, consisted merely of a few readily-available books about the couple and a typewriter, in a house they’d occupied for less than a year.

Most recently, in France, my partner and I undertook a quixotic search for a statue of Samuel de Champlain, supposedly located in his birthplace of La Rochelle. Of course, in Canada, interest in Champlain as a seminar figure in the history of New France requires no explanation and evidence of his influence is easy to find.

Indeed, during several summers on Nova Scotia’s Annapolis shore, I regularly biked in the early morning the seven or eight kilometres each way from Granville Beach to the re-creation of Champlain’s first settlement at Port Royal. I would gaze out at the river, imagining him beside me on that shore, almost half a millennium before, worrying about the viability of his little habitation. And of course, throughout modern-day Québec, where he was later able to make a more lasting mark, statues of Champlain and namesake structures abound.

Sadly, Champlain’s enduring importance in La Vieille France is somewhat less apparent. Although we were staying in La Rochelle at L’hôtel Champlain, nobody on staff was able to direct us to where his statue might be found. At the Musée du Noveau Monde nearby, there was scant mention of him in the surprisingly limited exhibits and text relating to New France. Ultimately, it was at the museum reception desk (manned by a helpful gentleman who’d been born in the New World, in Cuba) that we received regretful confirmation of the complete lack of Champlain commemorative statuary in La Rochelle. Nevertheless, the man assured us, Champlain had most definitely been born there, and only a street or two away was the Protestant church where he’d been baptized.

Back at our hotel, a search of the web confirmed that Champlain had indisputably been from La Rochelle—and most emphatically not the town of Brouage, down the coast, as once believed. Even so, it seemed possible to us that some visual remembrances of him might still exist there.

Brouage was once a citadel town, entirely enclosed within protective walls, of which there are now only remnants, with grassy bunkers and stone structures, similar to what the French built in North America to fend off the British. Brouage boasts a Rue de Champlain, as well as a Place Champlain, where stands a small house with a plaque explaining that it is often “confused” with a dwelling Champlain once lived in. However, the plaque fails to make clear where the great explorer did reside, if he ever actually once lived in Brouage.

And no signs of a statue. At the nearby restaurant where we had lunch, the wait-staff were good-naturedly unaware of a Champlain statue and unapologetic about it. At the Office de Tourisme, the young woman was apologetic when she failed to turn up any information about a statue, particularly because we were Canadians to whom Champlain’s legacy evidently meant something. She suggested there might be some material on him at the Catholic church.

We’d already traipsed past that church, at least three times, in our futile quest. Since Champlain had been baptised in a Protestant temple, it had seemed pointless to seek him in a Catholic holy place. However, we dutifully traipsed past the church yet again—and this time, thought to glance up at a tall, somewhat weather-beaten column, topped with a globe and boasting some nautical carvings, but no likeness of Champlain. However, on the base was a near-illegible inscription commemorating Champlain, as explorer, map-maker and foundational figure of la Nouvelle France. Who had been born in Brouage—at least according to the inscription, if not according to history.

So, if history is a lie, can we say that it’s the past that is fiction and the present that is fact? Or, is the real truth, as T.S. Eliot wrote, that “Time present and time past are both perhaps present in time future.” In which case, it may well be that for us—as well as for Champlain and John Steinbeck and Saint Dominic it’s the next destination that promises to be the best, the richest and the most rewarding.

VOUS N’AVEZ PAS LA PRIORITÉ –

And other lessons learned from La Vie et Les Voies au Sud de la France

Throughout France, road-signs that read “Vous n’avez pas la priorité” serve as a warning to motorists about to enter a roundabout. In the South particularly, with its history of successive civilizations, we might also take the words as a reminder of our come-lately place in the long procession of generations, and how many layers deep run the roadways that began as ancient animal tracks, then became migration routes and points of incursion for Julius Caesar and his armies.

THE CAMARGUE

Not that the ancient Romans could claim to have priority, either. Or, for that matter, be termed “ancient,” not when compared with the Greeks who preceded them—or the Ligurians, who pre-dated the Greeks, and whose history in Provence dates from at least the Neolithic era.

All the same, in the vast Camargue area at the intersection of the Rhône River and the western Mediterranean Sea, it’s the marks left on the landscape by the Roman occupation that are still most evident: In the remains of crumbled towers; in the traces of paths through tufty grasses that once were wheat fields; in the faint tracks across the wide marais where the Romans harvested their salt, and in the long, snaking remnants of dikes constructed millennia ago.

When my partner and I visited there and pedaled bikes along what’s left of those ancient digues, across a landscape of marshes and gorse and sage, we were reminded in some ways of bike rides along the dikes in Grand Pré, Nova Scotia, or the straight, narrow roads between the Magdalen Islands, with the blue waters of the Gulf of St Lawrence right next to the road on either side.

At the same time, glimpsing wild Camargue flamingos dabbling nearby in the sea and heavy-breasted storks along the shore, along with the fabled white horses grazing in the distance, feels like an experience unique in the world. An experience both immediate and impossibly ancient, since nobody seems sure when or whence those horses first evolved, or whether the first human arrivals on that vast salt plain were greeted by the gabbling cries of flamingos and treated to the sight of a flock airborne, displaying the vivid colours of their underwings.

The history of the Camargue, like much of France, is a mixture of Christian zealotry, pagan rites and mythology, in almost equal measure. One living embodiment of all those themes is the gypsy population, who converge on the village of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer for an annual festival to honour the three Saints Mary for whom the village is named—and in particular, their servant-girl Sarah, a symbol of their own powerlessness and lack of status.

As for the Marys, who they were (the Virgin Mary? Mary Magdalen? Mary of Cléophas? Mary Jacobe? Mary Salomé?) seems to depend on which source you consult. And how and when was it that the best-known village of the Camargue came to be named for them, and whether those are truly their relics in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer’s 12th century church… Qui peut dire?

However you like your Marian legends served, whichever admixture of piety, conspiracy and genealogy you prefer, there are trails to follow in that part of Provence, and questions in search of answers. Many of those questions are hazily, if not messily, connected to the “Holy Blood and the Holy Grail” hypothesis, which contends that Jesus and Mary Magdalene had children together, and that the descendant of one the offspring emigrated to southern France, bringing with him or her the “royal bloodline,” which later flowed in the veins of the Merovingian kings. Or, if you incline toward another theory: It was Mary Magdalene herself who, along with two other Marys related to Christ, came to be spirited, for their own safety, from the Holy Land, then transported by boat to the Camargue—with their handmaiden Sarah along for the ride.

CATHAR COUNTRY

But perhaps the most historically significant clash between mythology and orthodox religion began in the 1200s, with the commencement of centuries- long persecution of the Cathar sect by the Catholic Church. My own interest in the Cathars burgeoned when I began to look into the history of Saint Dominic de Guzmán, who plays such a significant role in the first of the two volumes of my novel-in-progress,“The Master of the Dog.”

Much about Dominic depends on whether you look at critical accounts of the actions of the clergy—particularly those of the Dominican Order he founded in 1215—or read modern Dominican panegyrics recounting his saintly life. Dominic either emerges as a fanatical persecutor of the Cathars, or as a gentle yet charismatic evangelist who preferred persuasion rather than persecution as a means to convert the Cathars back to the True Faith.

Of course, my own opinion of Dominic is a fiction-writer’s, tailored to the needs of my own narrative, not an historian’s view. The Dominic I imagine is conflicted, an ascetic and a visionary, magnetic in his ability to recruit followers and inspire them to join his Order. Yet, at the same time, almost willfully unaware of the power of his influence and what the consequences of his zealous faith might be.

Certainly, his was a tireless mission: Over the years of his ministry, he traveled much of Europe on foot—sometimes barefoot—recruiting priests and brothers to the Order of Preachers, (as the Dominicans were known in his lifetime), before returning time and again to his favourite monastery in Bologna to recuperate. More and more exhausted by his evangelical obsession, Dominic likely left the day-to-day running of the Order of Preachers to the abbots of the various new monasteries and convents he founded. Thereby acceding more and more to the militant direction in which his subordinates sought to take the Order, in active opposition to the Cathars and Waldensians and Bogomils and other divergent sects.

Of these, the Cathars were by far the most notorious. They believed in the equality of the sexes, even in their priesthood; they rejected fundamental tenets of the Roman Church, including the resurrection of Christ and the transformation of his body and blood into bread and wine. These were only some of a long litany of their heresies in the eyes of the Pope and his clergy. Even before Dominic came on the scene, purges and murders of Cathars—both men and women—were not only commonplace but continually on the upswing.

Late in the 12th century, years before he founded his Order, Dominic’s journeys from his native Spain took him all through the Occitanie and Provence, and along winding roads and steep paths past villages and shrines, some of which must have been belonged to Cathar communities. He would have seen children on their way to Cathar churches and schools—children who looked no different from Christian Spanish or Provençal children. And he’d have passed their parents—ordinary as any other parents—chatting at the communal well or hauling grain to a mill for grinding.

Perhaps Dominic would also have noted some Cathar churches and meeting-places pulled down or burned to the ground by the Pope’s men; Cathar storehouses looted, or even the remains of Cathar “good-men” and “good-women” lying by the roadside. Surely, had he seen these things, Dominic would have felt some compunction, might have decided that he would seek to exercise compassionate persuasion to turn these folks back to Christ—even if the Cathars did not hold Christ in the same divine esteem.

But even had Dominic started out with goodwill toward these heretics …once the Pope had given him the privilege of founding an Order of Preachers, for how long would his compassion have prevailed? That’s one of the questions at the heart of my speculations about his character.

Speculations that were assisted by a winding and climbing drive through that same part of Occitanie, over the same roads, re-dug, redesigned and repaved a thousand times since Dominic’s day. For my partner’s and my travels, the weather, as in much of France at the time, was wild, windy and wet with almost horizontal rain. Gene and I had to scrap our plan to drive up and up a steep peak to the rebuilt fortification of Montségur, remains of the last Cathar redoubt in the region, which had been initially besieged around the time that Dominic would have first passed by—and to whose lofty summit he might have climbed on foot, had he been sufficiently fit and ambitious.

Since we’d been forced to skip Montségur, we drove instead to Carcassonne, where the weather was similarly cold, bleak and wildly windy—although not raining quite as heavily. Still, trudging the cobbled streets of shops within the fortification walls, with the temperature registering about 3 °C, I found myself actively envying those Cathar clergy in times past, forced to mount a pyre of logs that were then set alight. At least, I thought, they’d have enjoyed a few moments of warmth up there, before the flames consummated their martyrdom.

A less drastic solution to the cold was to seek out the interior of the Catharism Museum in the nearby town of Mazamet.. The museum was not only warmer, but an excellent place to get a crash-course in the largely unhappy history of the Cathars. The vengeance of the auto-da-fé, for instance, seemed equal to anything the Spanish inquisitors dealt out in the following centuries. Those Cathars, especially clergy, who either refused to recant their beliefs, or who went back on their recantations, were routinely burned to death. And if they managed to somehow escape the flames and later died of other causes, their bodies were exhumed and burned posthumously. These brûlés sur le bûcher were intended “to horrify the public,” presumably with their evocation of eternal hellfire for all blasphemers.

That detail seemed not dissimilar from the story of the so-called “Saint Guinefort” of that period: the slain greyhound whose corpse, not long after Dominic’s death, became the center of a cult of worship in the Diocese of Lyon. On the orders of a papal inquisitor— a Dominican, it so happens, who’d possibly been recruited to join the Order by Dominic himself— the dog’s corpse was disinterred and then burned. Which ended neither the cult nor efforts of the Church to stamp it out.

As for the Cathars…the wave of persecutions and inquisitions overseen and conducted by the Dominicans appeared to swell after the founder’s death, continuing throughout the 13th century and beyond. While Cathar clergy were put to death, usually by fire, their lay followers who repented of their heresy were treated with more lenience: The inquisitors merely gave out penances, such as the compulsory sewing of yellow crosses on their garments. It was a similar form of humiliation to the yellow badges in the shape of the Commandments that, around the same period, Jews in Britain and elsewhere were forced by the Church to don. And which, in our own time, are recalled in the yellow Stars of David sewn to the clothing of European Jews under the Nazi regime.

THE END OF THE ROAD

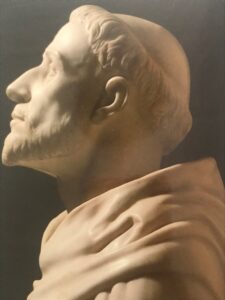

Whether one follows the trail of St Dominic Guzmán in a spirit of speculation, or in search of immutable fact, the road eventually leads to the former site of the monastery he founded in Bologna, to which he invariably returned between pilgrimages, and where he chose to die. The monastery exists no more; however, a basilica was built on the site not long after Dominic’s death to house his remains. There, inside an ornate “arca” on a specially built altar, his bones are said to repose. And within the arca, a reliquary is alleged to contain his skull.

I can’t say whether or not I believe that the earthly remains of Dominic do, in fact, lie in that arca, But merely standing on the site itself made me feel that I was at least in the general locality of something authentic, evocative of the person to whom it is dedicated. An actual person, however long dead, who, partly through religious mythology and partly by my own invention, has become oddly alive to me. In the San Domenico Basilica, I experienced a feeling akin to personal acquaintanceship—the same sensation I had experienced a year before, when, at the door of what had been his first monastery in Toulouse, I’d started down the path of Dominic’s clerical life.

Presumptuous, no doubt, to claim to know a real-life saint as personally as the hagiographers and the haters do, as well as more evenhanded historians. Yet I do believe, as all writers both of fact and fiction are obliged to believe, that to follow the road a character, literally or figuratively, is to learn his or her story. A story that, as writers of fiction in particular like to claim, is stranger than truth and realer than reality.

LES TEMPLIERS IN BIOT

Speaking of the easy intermingling of fact and fantasy, who could resist a two-day extravaganza of knights and fair ladies, wizards and vizards, heraldry and hijinks? Especially when there’s ample parking at the shuttle-bus site, transport by bus to the fairgrounds on the outskirts of the beautiful village of Biot, and a ticket of admission to the event itself—all of it absolutely free? Such is the annual siren song of an event known as “Biot et Les Templiers,” which advertises itself online and on posters with the countenance of a visored knight wearing the determined expression of a belligerent biker.

For instance, on the “cotedazur.fr” website, there’s a Chamber of Commerce-y vibe about a festival described breathlessly as a “manifestation historique,” taking place in “une veritable cité mediévale.” However, on the actual site, we found something almost Pythonesque in the costumes of the ticket-takers and bartenders and vendors (tabards for the men, wimples for the women) promoting everything from custom-crafted chain-mail (so many uses!) to homemade mead, to imitation relics.

Bypassing these Arthurian entrepreneurs, we went directly to the “medieval games”—a roped-off grassy area, surrounded by white pavilion-type tents and best overseen from a set of bleachers that would not be out of place at a Little League tournament. There, “knights” in simulated armor were being helped up by their squires onto the backs of horses caparisoned in summer-weight garb, in preparation for contests of skill. The whole atmosphere had a lighthearted quality, more evocative of a fun fair than the deadly seriousness of chevaliers out of the “Chanson de Roland.”

All the same, it’s not every day you get to see a real-live joust, with visored knights aboard spirited steeds. The excitement was palpable in the stands, especially notable in the woman sitting beside me— a hefty Niçoise with emphatically blonde hair and a sharp-cornered black purse she kept unintentionally pressing into my leg. She was friendly and voluble, very eager to talk about “les Templiers,” whom she characterized to me as heroic martyrs, who’d split off from the conventional Catholic church and were persecuted for it, down to their last leader, “tué par le Pape.” In her recounting, these Knights Templar seemed more similar to the Cathars than to the Ivanhoe-like heroes of the Templiers brochure.

However, when I later had a chance to look more closely into their history, it struck me that Hell’s Angels and the Mafia might be closer counterparts, in modern terms. Like so many initially well-intended enterprises, the Templiers had apparently started out with fairly humble intentions, self-described “pauvres chevaliers,” whose crest depicted two knights riding the same horse to proclaim the modesty of their means. They offered themselves as protectors of religious pilgrims and well-to-do laity making the hazardous journey to Jerusalem. But soon, the Templiers were not only charging handsomely for their services, they were acting as bankers of the fortunes that nobles left in their keeping while on crusade or pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

By the 14th century, the Templiers had evidently become too successful their own good, rivalling the papacy and the monarchy in power and wealth. Eventually, King Philip of France pressured the Pope at Avignon to seize the Templiers’ fortune and make them confess to heresies. Their last leader, Jacques de Molay, was burned at the stake—which did accord with what the Niçoise woman in the stands at Biot had told me. Still, her impression of why this had happened seemed more like religious martyrdom, than medieval—or modern—power politics as usual.

Clearly, the Biot et les Templiers extravaganza is no scrupulously accurate historical symposium on the moyenne âge. Yet, nor did it seem to us a crassly commercial event intended to rope in the tourists. Instead, it felt like a genuine celebration of what the French like to call “le patrimoine”—pride in their heritage—in this case, geared not to scholars but to ordinary French folk, happy to shell out for plastic swords and princess hats and rubber elf-ears right out of “Lord of the Rings.”

There were few foreign license plates that we could see in the vast free parking lots, few snatches of conversation other than in French, no translations into English or any other language on signs, menu cards or pamphlets, nor in announcements over the p.a. In fact, were it not for heavy-metal rock evocative of the World Wrestling Federation played at the climax of armed combats, and those “Game of Thrones” touches in the appurtenances and costumes sported by participants and spectators alike, we could almost have imagined ourselves, in a France, not so much of another time, but of a sensibility into which no other culture had ever intruded or ever would.

ROADSIDE ATTRACTIONS

Gene and I had arrived to spend a period of time in the South of France with the intention of improving our French. But it came immediately clear to us how many people in that part of the world speak English and—worse— are English. Or American. Or Europeans whose lingua franca is, regrettably, no longer Franca but English. And because of that, the long-term working population of restaurateurs, tradespeople and merchants, if not themselves English, all speak English in the normal course of business.

Meanwhile, the large supermarket in our neighbouring village of Plascassier boasts shelves bedecked with Union Jacks and devoted to such durable UK favourites as HobNobs and Branston Pickle and Weetabix. Farther along the shelves, beneath the Stars and Stripes, is a Tex-Mex section stocked with Old El Paso tacos and salsa, along with Hellmann’s Mayonnaise and Lay’s Potato Chips. (Which are pronounced “sheeps” by the French, thereby occasioning some initial confusion on the part of non-francophones as to whether it’s snack food under discussion, or mutton.)

But there’s more to Plascassier than the heavily Anglicized Super-Umarché. Surely there must be, considering that Édith Piaf chose this village in which to live out her final years. And although her gravestone, along with those of many other luminaries of the arts, can be found in the Père-La Chaise cemetery in Paris, the Street Sparrow is also well-memorialized in Plascassier. That’s at the Rond-point Édith Piaf”— a roundabout bearing not only her name, but also an arresting photo of Piaf with her characteristic expression of ecstatic suffering and hands spread in her signature gesture, both of acceptance and defiance.

One way the country remains proudly Gallic is in its habit of naming streets, public squares and even laneways to commemorate prominent figures in its political and military history, from Valéry Giscard d’Estaing to 19ieme Mars 1962, to Maréchal Foch and Charles de Gaulle. And of course, from even deeper in the past, the names of saints and icons and églises also adorn all types of transportation infrastructure, central meeting-places and pedestrian pathways.

Yet, most indisputably French of all, I think, are those highways and byways dedicated to the memory of artistes of numerous disciplines, including Jean Genet, Victor Hugo, Guy de Maupassant and….well, Édith Piaf. (A bit of an afterthought, I’m afraid. While 60% of French road names celebrate men, apparently only 6%, even nowadays, honour the country’s women.)

Ultimately, at the end of a long day on the road in the south of France, no matter what route you’ve chosen, no matter what kind of pilgrimage you’re on, no matter how backed-up the traffic or narrow the lanes or steep the rise, the path you pick is guaranteed to provide a link between the car-crazy present and that slower-paced past, when travelers trudged on foot or rode on the backs of donkeys or ambled in oxcarts to destinations of pilgrimage, stopping to pray or merely to take note of the roadside shrines and the grottos and markers and other memorials to those who’d previously passed that way.